Improving Lucas-Kanade with Super-Sampling

Table of Contents

What is Lucas-Kanade?⌗

It is an integral part of most visual tracking systems. Given two consecutive video frames, it estimates how something is moving from frame to frame. For example, this is the usual technique used to track how cars or people move in a video.

Lucas-Kanade can also be used to track how the camera itself is moving. If it’s assumed that everything in the camera frame is in the far-field (everything is mostly far away), then how the frame is moving represents mostly camera rotation. If the camera is rotating purely to the right for example, without panning at all, then all the pixels in the image are mostly moving to the left. Given these assumptions, a Similarity or 2-point parameterization is able to represent how the frame of the image is moving from frame to frame.

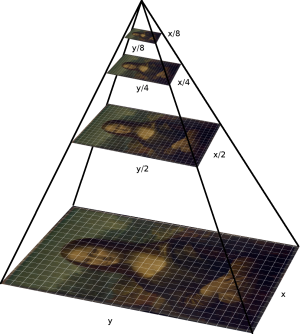

Assumptions made: When applying Lucas-Kanade, an assumption is made that the images are “almost” aligned within one pixel, if you scale both images down far enough. So for example, if a car moves 30 pixels left or right, then a Gaussian pyramid with 5 levels should have the car about 1 pixel away at its smallest level, since each level of the pyramid is half as large. We also assume that the car hasn’t changed shape much, or color, or brightness between the two frames. This means that without reformulating the problem in a major way, this algorithm is suitable for 30 FPS or faster video. Usually robust features like ORB, SIFT, or Learned Descriptors like Super-Glue are used to match very different images at lower framerate. Since it assumes that the input pixels are linear, it works best on raw images rather than tone-mapped images produced by a camera ISP.

So for the purpose of this blog post it’s essential to take away that Lucas-Kanade is based on an image pyramid, both for the image to warp and fit, and for the template image to match to.

This algorithm has been improved continuously because it has wide applications:

In “Lucas-Kanade 20 Years On: An Unifying Framework” (Baker & Matthews, 2003) the authors explore several ways to formulate and solve the least-squares problem, and conclude that what they call the Inverse Compositional Algorithm with Gauss-Newton Integration is the best option in most cases.

In “Differentiation of Discrete Multidimensional Signals” (Farid & Simon, 2004) significant improvements on the Prewitt, Scharr, and Sobel operators (usually intended for edge detection, but commonly used for image gradients too) are presented. Note that in the Lucas-Kanade formulation, using the much faster central-difference operator with kernel = [-0.5 0 0.5] provides a more accurate result since it is assumed the images are within 1 pixel of the correct solution, so smaller local neighborhoods provide more accurate results, and noise suppression can be provided by aggregating the contributions of many pixels instead.

In “Parameterizing Homographies (Baker & Kanade, 2006)” Kanade returns to explain that solving directly for transform matrices performs significantly worse than solving for the 4-point corner parameterization.

In “The Inverse Compositional Algorithm for Parametric Registration” (Sanchez, 2016) the author explores design choices for shaping the error estimate provided by each pixel to be more robust to noise and occlusions.

In “Direct Pose Estimation and Refinement” (Alismail, 2016) the author goes into full design details for how to select between different choices when implementing Lucas-Kanade. This compares different gradient calculation methods including FS2004 above. It also compares different types of image interpolation, which is the subject of this blog post. The authors find that bicubic interpolation has a noticeable impact on the speed and accuracy of convergence. And furthermore the author analyzes the effect of using dense, semi-dense, and semi-sparse pixels from across the image, rather than every single pixel. The authors also introduce the Bit-Plane transform that is useful for tracking marker patterns, which is probably how Vuforia works.

In “Fast and Accurate Gaussian Pyramid Construction by Extended Box Filtering” (Konlambigue, 2018) it is demonstrated that the Gaussian Image Pyramid can be formed more efficiently with only a small drop in quality using box filtering, which can be accelerated by summed area tables.

More on the application side, Google has released two papers on using Lucas-Kanade to combine video frames together for HDR and super-resolution of EO images, which is presumably how their cellphone photo app improves quality: “Handheld Multi-Frame Super-Resolution”( Wronski et al, 2021). Their prior work: “Burst photography for high dynamic range and low-light imaging on mobile cameras”(Hasinoff et al, 2016). They have a clever FFT-phase-based initialization for Lucas-Kanade, then proceed down the pyramid.

It is also worth mentioning the open-source DSO paper: “Direct Sparse Odometry”(Engel, 2016). It does not use Lucas-Kanade at all, but has an interesting way of selecting which pixels to use, which can be applicable to Lucas-Kanade as well.

Now that everyone is on the same page, let’s boldly try to improve on 30 years of work in 2021.

What is Super-Sampling?⌗

It just means that when resampling an image, the resampling is done on a super-resolution version of the image to sample. For example, if you want to warp an image you would first render the image 2x larger, and then sample from the larger image. This is commonly used for VR rendering for example because the rendered image must be warped to the shape of the lens in the headset, which stretches and compacts different parts of the image when it is resampled.

So it is well understood that super-sampling improves the quality of resampling but it is usually expensive to render a CG scene at a higher resolution, so the multiple is often smaller like 1.5x.

For a photographic image, how do we super-sample?⌗

To form a super-sampled Gaussian image pyramid, first upsample the image using any bicubic or learned method. Bicubic spline seems to work best to double or halve an image while preserving the details. Upsampling is fairly fast because it is separable: It can proceed first by doubling the width of the image and then the height for example, and the kernel is separable/1D and constant. Then form a canonical Gaussian image pyramid from the larger image by blurring the image and downsampling it 2x by discarding every other pixel.

Note that if implementing 2x super-resolution, the previous output of the algorithm can provide this upsampled image for free.

Improving Lucas-Kanade with Super-Sampling⌗

Following the efficient Inverse Compositional algorithm described by Baker & Matthews, we compute the image gradients, pre-compute the Jacobian images, and the Hessian from those, for each layer of the pyramid. Note these are all applied to the smaller template image pyramid that is not super-sampled.

Super-sampling is only applied at one place in the algorithm, where image warping occurs, which is the only place the image-to-warp is used at all. It does not matter how large the image-to-warp is, so super-sampling does not slow down the image warp, it only improves quality.

It seems to help most on images that have many fine details, a spiderweb of ocean waves, powerlines and so on. Based on the images used in synthetic tests, it can consistently make the difference between finding the correct transform, and diverging and failing.

How does Super-Sampling compare to Bicubic Interpolation?⌗

Both approaches should be used because they are both cheap and both provide noticeable quality improvements. Bicubic Interpolation is how a good resampler hallucinates what happens between pixels. Super-Sampling provides more real data that happens between the pixels.

Comparing the impact of the two, super-sampling has a significantly larger impact on quality than the interpolation method used, which makes sense because it’s introducing new real data. Bicubic interpolation improves accuracy on synthetic tests by about 25%. Super-sampling makes a massive 400% improvement in accuracy.

Bicubic interpolation is performed during image warping, which is done in the inner loop of Lucas-Kanade, and its cost increases with iteration count and image size. It reads from 4x4 pixels for each output pixel instead of 2x2 for bilinear sampling. It then computes a different kernel on the fly for each of these pixels using a mathematical function. Bicubic Spline is a popular choice, though Lanczos2 implemented with fast sinc() approximations provides a noticeably better result.

Super-sampling is performed once during pyramid creation, and increases the cost of forming the pyramid by 4x, but its cost does not increase after that point.

Bicubic interpolation is cheap to perform on the first few layers of the pyramid that are low resolution, so is certainly a good idea there. It is less clear if bicubic interpolation is a good idea to apply near the full resolution of the image as running more iterations might improve quality more for the same amount of processing time.

What other factors contribute to Lucas-Kanade succeeding?⌗

The number of iterations at each layer of the pyramid, and the target error make a huge difference in the rate of convergence. So making that inner loop as cheap and fast as possible is a good idea.

Reducing the number of parameters to estimate also has a huge impact. It is mentioned in several of the references that estimating for 2-point parameterization instead of 4-point parameterization yields more accurate results, when fewer points can be used. Also each parameter to estimate is another inner loop image dot product, so reducing parameters proportionally reduces the cost of the inner loop, and thus allowing more iterations for better convergence.